Navigating language barriers reveals deeper societal issues surrounding class and communication in Singapore.

I was at my community center last month when a bewildered woman in a green uniform approached me, holding her mobile phone. She asked if I could help translate a message to her client on the line. I agreed, only to discover that the call was from the delivery platform. The staff informed me that her account had been suspended for failing to upload her COVID-19 test result for the day.

I translated this to her, and she was taken aback. She explained that she had already uploaded it the previous night with her daughter’s help, but the platform staff insisted they hadn’t received it. Until she could successfully upload her test result, she wouldn’t be able to accept new orders, they stated bluntly.

Before hanging up, I informed the platform staff that their delivery partner could not communicate in English and was seeking help from strangers. I urged them to escalate the issue to their managers and consider training staff to handle queries in multiple languages.

The Translating Experiences That Shaped My Life

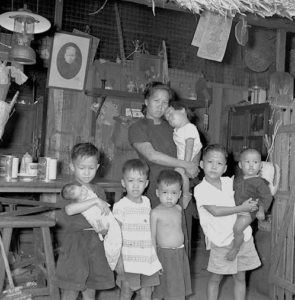

Growing up with parents who are English illiterate, I often became their translator. When I found letters addressed to them, I instinctively translated the contents. If they were too busy to listen, I would write little notes alongside these letters. In restaurants, I would translate menus, particularly when only English versions were available.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard people ask my parents, “Why don’t you speak English?” While I never felt frustrated about translating for them, I often wonder why others find it burdensome.

Looking back, I should probably highlight these 20 years of translating experience on my LinkedIn profile, showcasing my ability to make services more linguistically inclusive. However, it wasn’t until I became a working adult that I realized how much my parents were missing out on when I wasn’t around.

They couldn’t enjoy a blockbuster without subtitles, participate in local cultural experiences, or explore food and drink options beyond our neighborhood. If you’re skeptical, try spending a day without speaking a word of English, and you’ll understand.

Language as a Marker of Social Class

Under British colonial rule, Singapore was racially and linguistically fragmented. It wasn’t until after World War II that the government began to standardize education, leading to the adoption of English as the primary language for communication among the diverse population.

In his book My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey, published in 2011, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew explained the importance of English for trade and industry. By 1987, the major ethnic groups’ mother tongues were relegated to academic subjects, solidifying the divide between English-educated and non-English-educated citizens.

Despite the success of this “survival-driven” education policy, those who are not fluent in English often find themselves marginalized and labeled as lower class. This stigma can even extend to the belief that a lack of English proficiency is an inherited trait.

Once, after I developed a bad ear infection, my mother rushed to tell the doctor what had happened. I could tell from the doctor’s confused expressions that she wasn’t fully understood, so I stepped in to repeat everything in English.

“Oh, your daughter can speak English?” the doctor remarked, which I found rude. My mother, either oblivious or accustomed to society’s views, replied, “Yes, because she goes to school.” While my parents may not have degrees and have worked as blue-collar employees all their lives, I struggle to understand why language—a mere communication tool—has become a class identifier. Those who speak English are often regarded as superior, while others are belittled.

It’s ironic that while we take pride in Singlish, we simultaneously ostracize languages beyond English. We’re losing our “bilingual competitive edge” not due to a lack of resources for fluency in both English and our mother tongues, but because our meritocratic system leads us to believe that English is the only means to achieve a higher social status.

Moving Forward

I question whether language or sincerity matters more when interacting with those who don’t speak the same language. My parents have thrived in their workplaces despite their lack of English skills, demonstrating that mindset is key. While English fluency has practical benefits, it shouldn’t be viewed as a status symbol.

I hope my child will grow up in a society where learning languages stems from genuine passion rather than the need to conform or enhance one’s status. To achieve this, we need to extend kindness to those who are English illiterate in Singapore.

Upon investigating the linguistic services offered by various establishments, I found that many performative actions were taken with little follow-up. For instance, the delivery platform I mentioned earlier seemed more concerned about whether I would name them or compare them to others rather than providing a concrete solution.

After reassuring them that I wouldn’t disclose their identity, they informed me, “We provide help in English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil through our main support hotline.” They also mentioned their message service was “automatically translated to ease communication,” yet they failed to address how these measures work in practice on the ground.

Perhaps we need more awareness. Thanks to initiatives like the “Speak Good English” campaigns, English has become increasingly prevalent. While I support such government efforts, I believe we can advocate for improvements in both written and spoken English while also celebrating those who are still on their learning journey.